Letters from war

|

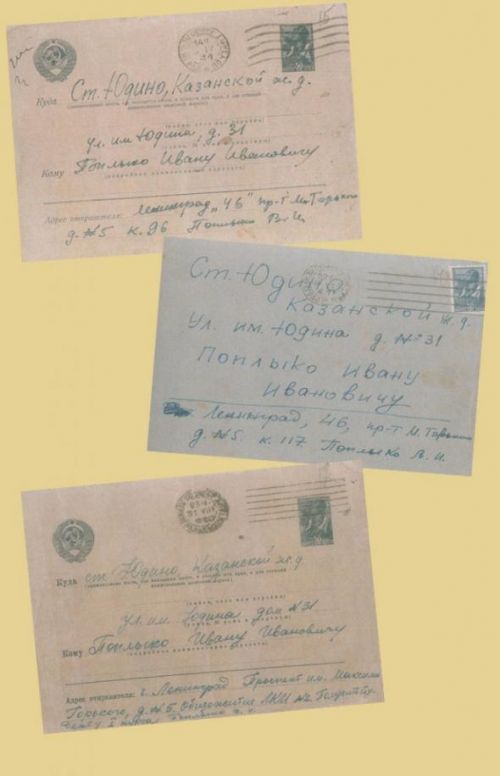

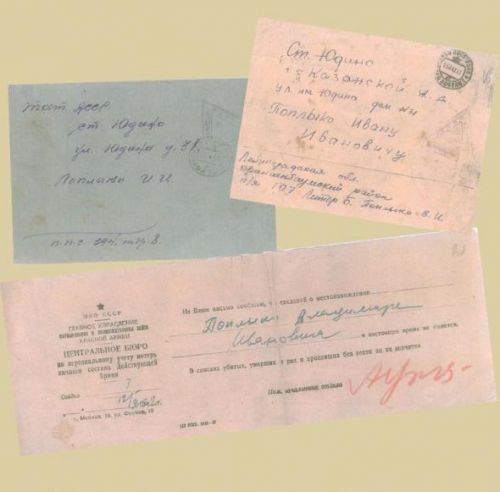

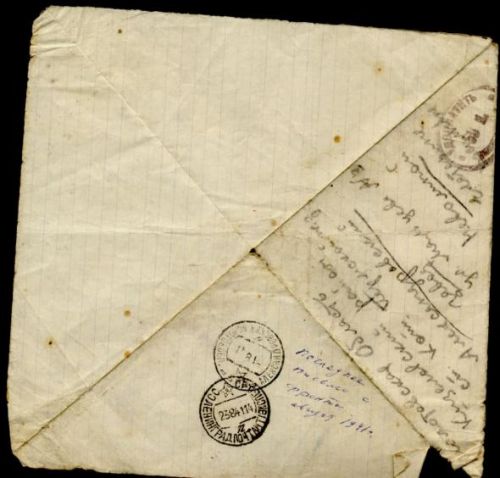

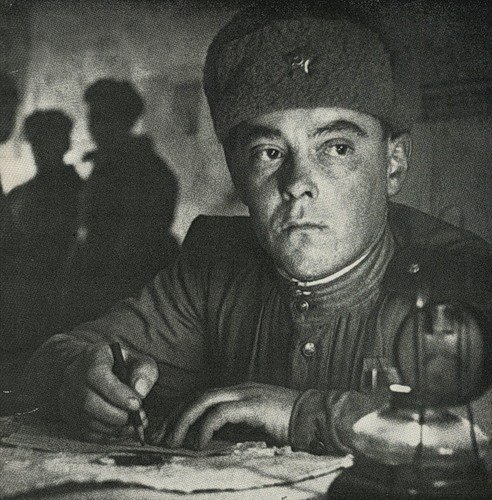

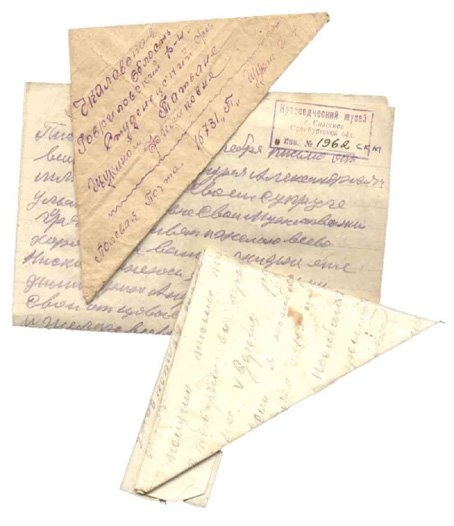

Old paper is wrapped in folds sagged more than sixty years ago. Ink is faded, printing color on postcards paled into significance. Letters from the Front are still enchased in many families. Each triangle letter has its own happy or sad story. It also happened that sometimes the news from the front that people were safe and sound came after the terrible official government envelopes. But wives and mothers believed: death notices came by mistake. And they were waiting for years and decades.

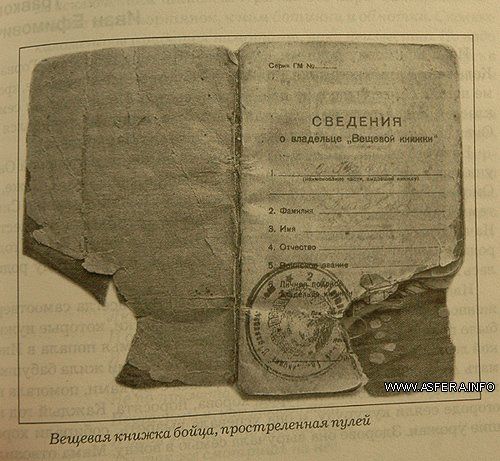

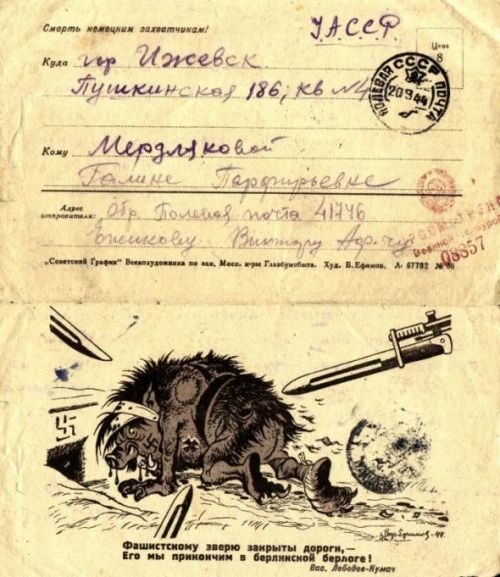

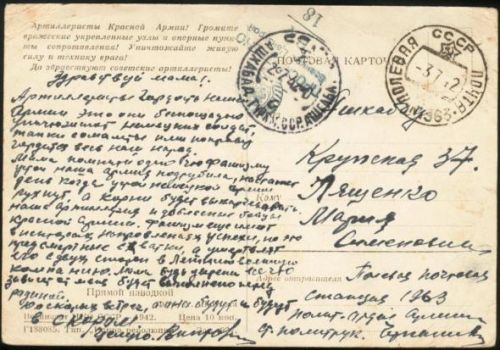

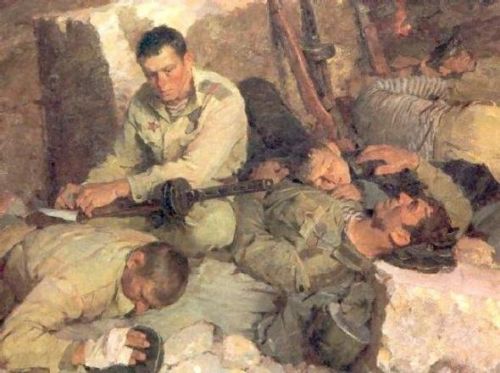

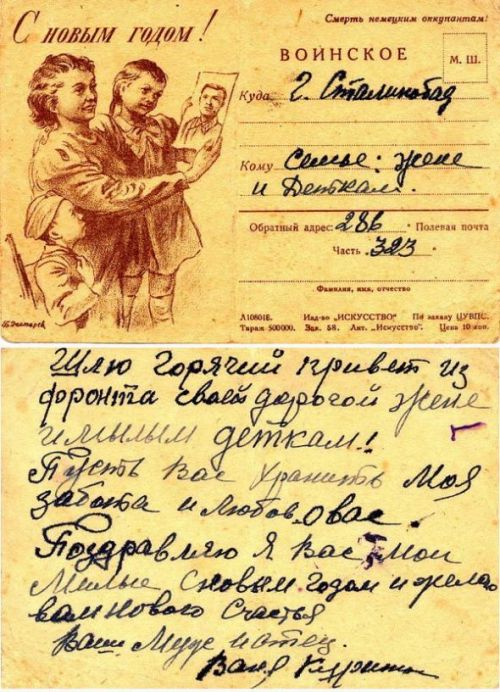

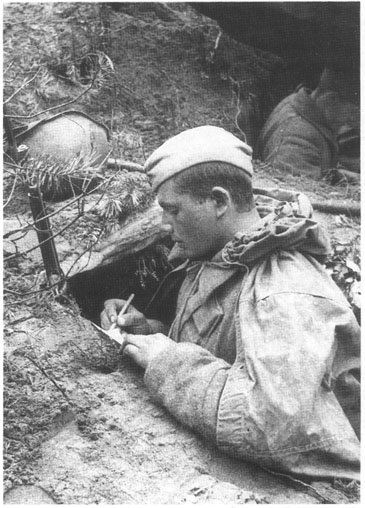

Letters from the fronts of the Great Patriotic War are the documents of enormous power. In the lines smelled of gunpowder you feel a breath of war, severe trench roughness of everyday life, tenderness of a soldier’s heart, faith in victory ... During the war much importance was attached to the decoration of mail linking the front and rear — envelopes, postcards, paper. It is a unique artistic chronicle since the war years, appeal to the heroic past of our ancestors, a call for the relentless struggle against the invaders. 16-year-old Sonia Stepina not immediately decided to write a letter to the front her former mathematics teacher, Mikhail Yeskin and confess her love for him. And after only a few letters received by the school staff from him, Sonia sent some word to Mikhail. She wrote, “I often remember your lessons. I remember how I was shaking and trembling with every sound of your voice ...” And soon, platoon commander Mikhail Yeskin answered Sonia, “I read your letter with great joy. You cannot imagine how happy the people are here reading letters from their friends and relatives” Conversation was constant. When Mikhail told Sonya that he was “a little scratched and rested in the medical battalion”, she eagerly replied, “I would have flown to you if I had wings ...” Young people fell in love. This correspondence lasted nearly three years. In 1944, Mikhail and Sonia got married.   The war did not spare anyone. And it dealt cruelly with this family. Two Vasily’s brothers died during the war years. His sister Maria lived in Leningrad, where she was in charge of a kindergarten. During the crossing on the “Road of Life” the car with the children disappeared under the ice from shell attack right in front of her eyes. Shaken by what she saw Mary lapsed into serious illness and died in 1947. Brothers of Vasily Volkov’s wife were killed in battle. Sen. Lt. Vasily Volkov died a heroic death in 1943. It was difficult to Mania Volkova. Zoya at that time was only 10 years old, her sister Valya — 7, little Kolya — 3 years old. Today it is almost impossible to find a museum or archive, which would not have kept the soldiers’ letters, which sometimes the researchers have not studied yet. But the history of World War II through the eyes of its members is an important historical source. And experts believe that the work of collecting letters from the front must continue, because the savers of soldiers’ letters die. Retired Major from Moscow, Yuly Lurie has been collecting letters of soldiers for nearly 60 years. The first letter in this large collection was his father’s letter, which Yuly’s family received in 1941. At that time Yuly was a teenager. Lurie’s collection includes a lot of front letters — from soldiers’ to marshals’. Thus, ordinary soldier Vitaly Yaroshevsky referring to his mother wrote, “If I perish, I’ll perish then for our country and for you” Petr Sorokin missing in 1941, managed to write a few letters to his relatives. Here is an abstract from one of the letters, “Hi, Mom! Do not worry about me ... I've already passed baptism of fire. When we are in Kronstadt, I will send you some silk for a dress” But he did not have enough time. Squadron Commander, Alexey Rogov who made more than 60 flight missions, sent the news to his wife and a small son. Every his letter was full of genuine love and concern for his relatives. “My girl”, Alexey wrote from Novocherkassk. “Prepare yourself for separation. 1942 is ahead. Live and hope to meet. So do I” The next letter he sent home from the Moscow region, “Hello, Verusinka and my dear son Edinka! Verushechka, please, don’t sing the blues. Get ready for winter. Buy our son boots and sew a coat. I love you. Alexey” The last letter was dated the beginning of October, 1941. Alexey wrote it a few days before his death. He was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union posthumously. Nicholay Dronov who died near Kerch in 1942 dreamt to come to victory. “... There is no free time. I have to learn many things in working order. But do not despair. We are going to win. Mom, dad and grandmother, do not to worry for me. Do not cry. Everything is all right. Your son Kolya”  Guards Sergeant Major, Natalia Chernyak fought until the very victory. In her letter to her mother she wrote, “Dear, Mom! Yesterday we had a big celebration in the part. Our body was handed Guards banner. Mommy, I was given a new pair of boots. My 36th size. Imagine how happy I am. It is 3 am now. I am on duty and I am writing to you. When I have some free time I read Mayakovsky. Oh, I almost forgot, Mom, send me notes of Strauss’s waltzes, “Voices of Spring”, “The Blue Danube”, the Ukrainian and Russian songs. It is necessary for our orchestra” A family of Muscovites, Zenko has long kept letters from the front of Fadey Zenko. And then his relatives handed them over to the museum. Fadey Zenko died shortly before victory. His letters were addressed to his wife Anna and children. Together with members of the Institute of Railway Engineers, she was evacuated to the Urals. Anna, with her two children moved into the village where she was elected deputy chairman of the kolkhoz. It was hard, very hard. But her husband’s letters helped her to survive. He was worried about how his wife and children would suffer the Ural frosts, “It is wonderful that you purchased felt boots. It is necessary to make hats with earflaps, so that our kids would not freeze. Anya, do not forget to think about yourself” Great desire to protect the wife and children from adversity is felt in the letter. Fadey Zenko’s children remembered that their mother while reading the letters from the front then cried then laughed. They charged her with their optimism. There were not enough people in the kolkhoz; there was plenty of equipment, and difficulties with the seeds. Anna Zenko, a former engineer of one of Moscow’s leading institutions, was not easy to adapt to rural life. The fact that she worked hard, was written in the next letter from her husband, “I found out, Anya, that reviews of the district managers of you are good. I am very happy and proud. Your success is our success” Many war postcards were accompanied not only by images but also the official Stalin’s quote, “We can and must clear our land of Hitler’s evil” People wrote in letters and postcards, bringing victory, “I’m going to beat the enemy to the bitter…” “... I will avenge the destroyed village”, “I believe that we will even upon Fritz”, “Mama, The Nazi invaders run away from us, we broke their teeth”... There was lack of envelopes. Triangle letters came from the front. They were sent for free. A triangle is a plain sheet of paper which was initially folded on the right, then on the left. The remaining strip of paper was inserted into a triangle. Letter writing of that time has long ceased to be a personal matter. This is history. The historical museum of Roslavl has a large collection of wartime letters. Nikolay Ievlev wrote his letter home 3 weeks before the war, “Mom, do not worry about me. Everything is all right. It is unfortunate that nobody can look after our garden. We have wonderful apple trees. Our military school is surrounded by very beautiful woods. In the morning it is possible to see some elks. Leonid Golovlev could not find his family for almost two years. Only in 1943, his relatives received a letter from him, “I did not know anything about your destiny, and I was worried. I cannot imagine how you survived the occupation. Let’s hope for the best. What can I say about myself? At war. Alive and well” Leonid has been missing since 1944. Nikolay Feskin’s letters are full of father’s love. In the rear, he left wife Evdokia and three children. Here are a few phrases from the soldier’s letter, “... I kiss you many times. I want to see very much. I dream of children – Valya, Vitya and little Mirochka”  Man always remains man, even in the toughest conditions. During the war, young people often corresponded in absentia. Thus, an officer of the army sent to unknown Ekaterina Kataeva a letter from the front. Ekaterina said recalling the time, “Our grooms were killed in the war. My boyfriend was killed at Stalingrad. And then a letter from Semyon Alekimov came. Initially I did not want to answer. When thinking about our soldiers at the front, about their battles and how they were waiting for letters, I decided to answer” Katya had a grueling time. There were five of them. Their father died in 1936. The more the young people corresponded, the stronger their feelings became. Senior lieutenant Alekimov was on the verge of death at various times. Remembers how miraculously he survived during the bombing when their platoon crossed the river Berezina; how they were under the German aircraft’s fire. After the war, Semyon Alekimov said, “Ten lives and ten deaths you live out in one day in the war. But always I dreamed of my Katyusha” Katya and Semyon managed to survive all the hardships, and then the fate united them.  Soldier Vladimir Trofimenko informed his relatives in the Sumy region, “We have dealt a severe blow to the Germans at Bobruisk. I wish the 1944 were the last year of the war. Now the Germans raise their hands in front of us — young soldiers in dusty tunics. I now see future time of peace, I hear singing girls, and laughing children ...” This letter, along with the other news from Vladimir, was handed to the local museum. Over the years the paper has become quite clear. But the author’s words are clearly visible. There are some crossed out lines in the letter. The work of censorship. “Checked by the military censor”, such notes are everywhere. Back in August 1941, The Pravda newspaper wrote that it was very important for every letter to find its destination at the front. And further, “Every letter, parcel ... enliven our fighters, inspire them for new exploits” It's no secret that the Germans destroyed the communication nodes and telephone lines. There was a system of military field post under the Central Directorate of Field communications. During the first year of the war the State Defense Committee adopted several decisions related to promotion of correspondence between the front and rear. In particular, it was forbidden to use mail transport for fatigues. Post carriages were hitched to all the trains, even the military echelons. The service of military postal workers was uneasy. The staffing position of the postman was known as a forwarder. Postman Alexander Glukhov came up to Berlin. Every day he went around all the parts of his regiment, collected letters written by soldiers, and delivered them to the field post. He had a huge bag. There was always a place for cards, paper and pencils for those who did not have time to stock up on these necessary things. Many years later Alexander Glukhov recalled that he knew the names of many fighters. However, after almost every battle there were losses. Already at the headquarter he put the mark “is out” on the letters which didn’t come down to the recipients. It was not easier to work as a postman in the rear. Valentina Merkulova was appointed a post-woman when she was in the 4th grade. Before dinner she went to school and after school worked. From the village of Bulgakov, in the Orel region, where she lived with her sick mother, the girl set off with letters to the nearby villages every day, rain or shine. Later, remembering the war, Valentina shared her impressions with readers of a local newspaper, “I had no warm clothing, but my mother got a coat and rubber overshoes from some neighbors” Even then, young Valentina had to deal with grief and joy. Some read letters to the entire village or the countryside. Everyone interested in news from the front. But there were many funerals. And the trouble did not spare their family. Valentina’s mother lost two brothers. Valentina’s father died later, when he came from the front. On the eve of Victory Day people were waiting for the letters with special sense. Armenian Edward Simonian fought in a tank brigade which was part of the Stalingrad Corps. In 1944, there left only 7 people in their team. More than once he was wounded and was in hospitals. At the end of the war his mother received a notice of his death. Then suddenly for her a letter arrived, the coveted triangle, in which Edward wrote: “Dear Mom, I got shot in Latvia. I was in hospital. My wound on the left leg is slowly being tightened. Soon we will win Nazi and start living happily and cheerfully”

And this is from a letter of Mikhail Martov on May 9, 1945, addressed to his wife, “Dear Tamara! I did not sleep all night. All the weapons were reverberating. Here it is! Victory! It happened! We dreamed of it all these years ... We are now in East Prussia. It is beautiful here, spring”

Artilleryman Nikolay Evseev wrote his relatives, “On May 9, along with my comrades in fight I returned from Vienna, but the car broke down on the way. Everybody got out. And we heard shooting somewhere. The trail went across the sky, then — the second ... That’s when it became clear — it is the end of the war!” Today, almost every family has a box with the front-line letters, photographs and military awards. Each family has its own story. But they are all united by one thing — total involvement in the tragic events of World War II. Until now, letters from the front, burned, torn and half-rotted, touch us deeply. Over the years, the lessons of that war — bitter and victorious — have not been forgotten. And each time on May 9, words “The feat of the people is immortal” sound somehow specially.

|